Sin and Socialism: Can They Be Reconciled?

“Man's capacity for justice makes democracy possible, but man's inclination to injustice makes democracy necessary.” - Reinhold Niebuhr

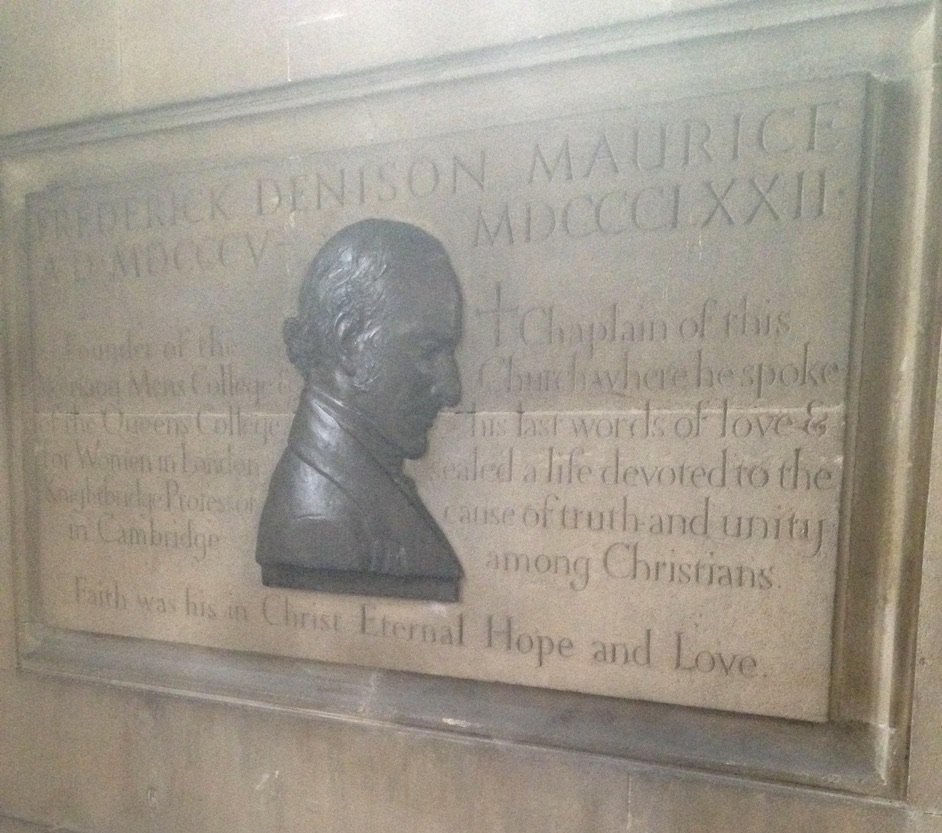

Among the many illustrious former vicar-chaplains of St Edward King and Martyr is one whom many regard as the father of the modern Christian socialist movement: F. D. Maurice. Christian socialism arose in mid-19th-century England in response to the growing social challenges and injustices brought on by industrial capitalism. The movement within the Church of England sought to renew the religious and moral basis of the nation. Maurice and his allies attempted to inject a Christian moral perspective into the new field of inquiry known as political economy by holding up the ideals of cooperation, brotherhood, equality, service and more. The effects of the movement reverberated into the 20th century, shaping William Temple's social vision and the policies of the Labour Party post-World War II.[1]

While there is much of value in the theological and moral thought of Maurice and the first generation of Christian socialists, there is much that can be critiqued. The movement was often guilty of paternalism, a moralistic attitude to poverty and more.

But perhaps the most significant lacuna that exists in their corpus is one that has beset the socialist project more generally: accounting for the limitations imposed by human nature. Even for people like Maurice, R. H. Tawney, or the Social Gospel advocate Walter Rauschenbusch, who did take sin seriously (and especially its manifestation in capitalism), there is little attempt to address how the limits imposed by original sin are accounted for in their economic and political proposals. The theologian Brad East has asked the right questions in this regard: “What is the relationship between the Christian doctrine of original sin and Christian support for a socialist economy? What role does ineradicable human fallenness play in such an account of socialism's operation and success? Is ‘human nature’ and/or the limits and/or sinfulness of all human beings without exception a determining factor in the Christian support for, or version of, socialism?”

From the 19th century to today, an idealism and optimism about human nature and social progress has permeated the various streams of socialism, Christian or not. This has left socialists vulnerable to the charge of utopianism, often for good reason. A 2019 article by Theodore Dalrymple in the National Review exemplifies this attitude: "Socialism is not only, or even principally, an economic doctrine: It is a revolt against human nature. It refuses to believe that man is a fallen creature and seeks to improve him by making all equal one to another."

This article attempts to make an initial response to these types of claims by arguing for the compatibility of the Christian doctrine of original sin and participatory socialism, or economic democracy. After briefly laying out how I will use the terms socialism and original sin, I will outline and critique the case made by the prominent neoconservative Michael Novak regarding original sin and capitalism. Then, drawing on Reinhold Niebuhr's Christian realism, I will present a realist case for socialism. Whatever other objections to a socialist political economy may arise, this paper aims to show that the issue of human nature need not be an obstacle. I will close with some brief remarks on the vision’s broader feasibility and prospects.

Note that the argument presented here is primarily theological and focused on the issue of human nature. As such, I will not be addressing the important arguments about the morality and justice of alternative economic proposals. Nor will I address the host of empirical questions which arise regarding human economic behavior. There may be many reasons – moral, practical and theoretical – to avoid economic democracy, but my argument seeks to show that human nature is not one of those reasons.

Defining terms and desiderata

Can a realist theological anthropology of the broadly Augustinian tradition be reconciled with economic democracy? To move towards an answer, let’s first define some terms.

This article is interested in "socialism as a philosophy regarding normative property arrangements and decision making in the larger economic and political community."[2] Among the various socialist visions, I will not be dealing with the statist, centrally planned economies seen in the likes of the Soviet Union or Cuba. This was only ever one stream of socialism, and has few defenders today. I am interested in the form of socialism which can be called "participatory socialism" or "economic democracy" which is distinct from Soviet or Cuban socialism in that it is 1) democratic and 2) decentralizes most ownership and management to the level of firms. This form of socialism has affinities with various theories and movements, including anarcho-syndicalism, guild socialism, distributism, the Italian nineteenth-century 'associationism' in the civil economy tradition (Genovesi) and more. The means of production in participatory socialism are owned and managed by workers. This could take various forms, but the most common type of socialist enterprise is generally a cooperative, but a participatory vision can include small-scale "private" firms and large-scale firms (such as natural monopolies) owned by the state.

What about markets? Socialists disagree about the desirability of markets, but it is important to say is that they can be integrated with economic democracy. In some proposals, they are retained as efficient mechanisms for allocating goods and setting prices.[3] Some participatory socialists find that the same ends could be achieve through participatory, bottom-up planning methods.[4] The question of markets does not directly affect my proposal and so it will not be addressed here.

Original sin will be understood in a broad sense, referring to the corrupt nature inherited by all human beings. It is the incurvatus in se ("curved inward on oneself") that cannot be eradicated in this life, not even in those redeemed by Christ from the power and penalty of sin. To be curved in on oneself is to be self-centered, to follow the “devices and desires” of one’s own heart above love of God and neighbor. Fallen human beings are certainly not incapable of virtue, but their intentions and actions are always imperfect, tainted by sin.[5]

Having defined these terms, I suggest that a realist account of political economy will need to fufill two requirements with regard to sin:

1) The "defensive" requirement. Sin gives rise to the will-to-power among individuals and groups, which means that defensive power of countervailing forces is needed to provide checks against abusive and aggressive uses of power. This is a typical justification for political democracy.

2) The "harnessing" requirement. Because of the fall, humans beings have an ineradicable tendency to pursue their self-interest. This means that a political economy cannot entirely divorce personal effort from financial or other gain. This rules out strict egalitarian forms of political economy, though there are other forms of motivation which are not material and the relative importance of these may vary in different contexts. Thus we stipulate that any viable economic system needs to account for and harness the self-interest which is a drive of human economic behavior.

Novak's realist case for democratic capitalism

The American Roman Catholic philosopher Michael Novak has been the among the most prominent and influential defenders of capitalism among Christian thinkers. He saw himself as carrying on the Niebuhrian realist tradition, writing that "Niebuhr did not give much attention to economic issues. Precisely in Niebuhr’s neglect, I found my own vocation."[6] Novak's best known work from 1982, The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism, has received ample critique and analysis which I will not rehash here. Yet his account remains exemplary of the argument against socialism on the basis of original sin, and I will focus narrowly on this aspect of his book.[7]

Novak's account of original sin and its relationship to capitalism has three primary claims (82ff). The first is that sin is ineradicable from human nature. We can never expect humans to act wholly altruistically in this fallen world, and a viable economy theory needs to incorporate this fact because "Every form of political economy necessarily begins (even if unconsciously) with a theory of sin" (349).

The second claim is that the defeat of sin in a capitalist economy comes from "transforming its energy into creative use," which results in the "unintended consequences" of benefitting the common good in wealth creation (82). This is a version of the Stoic and classical liberal idea of the "invisible hand" guiding the self-interests of individuals in such a way that benefits all. The system thus does not require perfect virtue or that the intentions of its actors be for the common good which results. Selfishness can be harnessed for good.

The third claim is that self-interest is not a purely negative feature of human behavior but includes moral virtue. Novak claims that individuals' "real" interests are "seldom merely self-regarding" (93). They frequently prioritize their families and give weight to the importance of their communities. Novak goes on to say that "In the human breast, commitments to benevolence, fellow-feeling, and sympathy are strong." adding that democratic capitalism "depends upon and nourishes virtuous behavior" and depends upon a "high degree of civic virtue in its citizens" (85). How does this relate to original sin? "The concept of original sin does not entail that each person is in all ways depraved, only that each person sometimes sins. Belief in original sin is consistent with guarded trust in the better side of human nature. Under an appropriate set of checks and balances, the vast majority of human beings will respond to daily challenges with decency, generosity, common sense, and even, on occasion, moral heroism." (351)

What are we to make of these three claims? I do not wish to dispute the first claim about original sin which I take as a given for realists. There is, however, a real question about how it might relate to the scope of what Novak includes in his third claim. His point about self-interest having a wider scope than the self is correct and we shall return to it. But given how much virtue, decency, and fellow-feeling Novak claims is necessary for democratic capitalism to work, how strongly are the effects of fall felt in economic behavior in Novak's account? With the exception of the strong versions of Enlightenment and liberal optimism about the perfectibility of man, it is difficult to see how Novak's vision of democratic capitalism is any more "realistic" about human nature than many socialist theorists.

Novak's second claim about transforming sin's energy into creative use would appear to satisfy the "harnessing" requirement. He sees that self-interest can motivate productivity for selfish reasons. Let us concede for the sake of argument that a capitalist political economy does harness self-interest in this way. The problem I see with Novak's account is they he does not show that the capitalist organization of ownership and management is the only or even best possible arrangement for harnessing of self-interest.

The reason, I suggest, is that when it comes his analysis of socialism, Novak unfortunately deals almost exclusively with Soviet-style state run economies. Even when engaging theologian Jurgen Moltmann's socialist proposals of economic codetermination (where workers are included on decision-making boards) and the control of economic firms by their workers, Novak immediately reverts to the idea that this is "government control over life" and over "economic decisions" (270). The binary of government vs private ownership is deeply embedded in his thought.

The one place where Novak does address something like participatory socialism (209ff), his primary concerns have nothing to do with human nature as such and whether sin can be harnessed. He offers the contradictory points that 1) there would be too many meetings (which people don't like, as they don't really want to participate in politics) and 2) that Americans already have lots of associations and committees (which meet!). Here Novak seems to nearly repudiate the notion of democratic politics as such while also acknowledging that people are already engaging in similarly activities as would be required in participatory socialism.

But perhaps the biggest weakness of Novak's account is his treatment of economic power. While Novak acknowledges the concentration of economic power as an issue, he claims that competition and especially the "hazards of economic mortality" (90) will prevent inordinate amounts of economic power from accumulating.[8] Apart from being historically and empirically dubious, Novak fails to see the multidimensional nature of economic power: between unequally sized firms, hierarchical/top-down power within firms, and in individuals enriched by firms. It is likely that this is downstream of his overly individualistic account of original sin. For Novak, sin is essentially personally vice. A broader understanding of evil in systems, in the principalities and powers, may have made him more aware of the need for structural remedies, such as creating countervailing forces (law and other institutions), against sin.[9] This is precisely where the realist impulse behind political democracy calls for some kind of equivalent in the economic sphere. But because Novak doesn’t adequately consider that option, he fails to provide a convincing route for fulfilling the "defensive" requirement.

In light of this latter weakness in particular, I turn now Niebuhr.

A Niebuhrian realist take

One of the central concerns of Niebuhr's realism was the danger of the concentration of power. As Larry Rassmussen has written, "whatever one may wish to say about Niebuhr’s democratic socialism, and (the shortcomings of) his allegiance to democracy in the mode of political liberalism, he was never wrong about the necessity of democratizing economic power."[10] For Niebuhr, the presence of sin in human power relations necessitates a democratic accountability. The realism driving his democratic commitments in politics applies equally to economics.

Thus Niebuhr can write of the Austrian economist and philosopher Friedrich Hayek that he has “no understanding of the fact that a technical civilization has accentuated the centralization of power in economic society and that the tendency to monopoly has thrown the nice balance of economic forces — if it ever existed — into disbalance.”[11] While Niebuhr's concerns are arguably grounded in the historical facts, they also capture the logical and needed extension of the realist perspective on political economy. That extension is expanding the scope of defensive power against sin by democratizing the ownership and management of economic power.

Niebuhr was an ardent state socialist at the beginning of the 1930s, but he had left the Socialist Party by the early 1940s over its pacifism and became less adamant about the ideal of economic democracy. Nonetheless, in The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness in 1944, he has an insightful essay called "The Community and Property" which points to a realist position on economic democracy.[12]

Niebuhr writes that in a modern, technologically advanced societies, capitalism has led to the socialization of production. "The 'private' ownership of such a process,” he writes, “is anachronistic and incongruous; and the individual control of such centralized power is an invitation to injustice."[13] He continues: "Since economic power, as every other form of social power, is a defensive force when possessed in moderation, and a temptation to injustice when it is great enough to give the agent power over others, it would seem that its widest and most equitable distribution would make for the highest degree of justice.”[14] Niebuhr goes so far in his push to check concentrations of economic power, in socialist or capitalist orders, that he even says “it may be wise for the community to sacrifice something to efficiency for the sake of preserving a greater balance of forces and avoiding undue centralization of power.”[15]

Yet as Gary Dorrien writes, Niebuhr's "it would seem" was a retreat, a move away from the idea of economic democracy.[16] Niebuhr would eventually settle on the best workable scenario being not a full democratization of economic power but the countervailing power of big business, big labor, and big government. This in the end, isn't so far from the democratic capitalist position offered by Michael Novak. But I suggest that a Niebuhrian realism should follow the logic of his insight favoring "the widest and most equitable distribution of economic power" and propose a shared ownership and management of economic firms. In contrast to big, privately- (or investor-) owned companies, democratically owned and managed firms would decentralize power into smaller, independent units. The will-to-power domination that realists worry about would thus be held in check 1) between the more equally sized competing firms, 2) internally within the firms as ownership and managerial power is more widely distributed among the employees of the firms, 3) in other spheres of society as the deconcentration of wealth spreads spreads power more widely.

Incentives: Harnessing the incurvatus in se in participatory socialism

A final question is how a sin might be harnessed in economic democracy. There is disagreement among participatory socialists over whether remuneration is the same for all workers. For those who favor more egalitarian remuneration, the question is whether other incentives could sufficiently harness sin to maintain productivity. As Michael Novak noted, like Adam Smith and many others, self-interest is not to be equated with a selfish or profit motive. It incorporates a range of concerns: the well being of one's family and community, but also seeking the approval of one's peers, social recognition for one's accomplishments, and so on. And interestingly, Daniel Pink has summarized research that suggests internal motivations such as autonomy, mastery, and purpose are important drivers of productivity, especially in knowledge and creative work.[17] All this to say, humans' inward curve can find various routes to self-satisfaction, and non-financial motives are important for productivity regardless of who owns and manages the economy.

Yet it behooves socialists to assume that financial self-interest will affect worker productivity. As Stephen Mott, the ethicist and Biblical scholar who has addressed these issues in perhaps the most detail, has said, "Socialism needs to be kept down to earth by a vigorous penetration of democratic realism. Human beings are attracted to shared production not only by altruism and communal longings. They also are motivated by self-interest in the profits of the firms in which they would have a share."[18]

In more market-oriented proposals for economic democracy, cooperatives still compete and seek profit. Those profits are simply shared among the worker-owners of the firm and thus provide personal material incentives. This is true of cooperative firms today operating in capitalist market economies and would be true of firms in participatory socialist market economies. Participatory models also tend to include different levels of pay for different tasks and roles – though the pay ratios are far more equitable than in capitalist firms.[19] There is thus no reason to believe that material incentives for productivity would disappear in a socialist economy.

Mott's defense of socialism guided by Christian realism points out that worker ownership and management certainly does not solve all problems, and it creates new ones. For example, some interpersonal conflicts are likely to increase as power is more equally distributed. The decrease in alienation from one's work can also bring with more stress. A stronger sense of responsibility can increase the chance of burnout.[20] There are certainly other avenues in which sin will manifest itself in economic democracy. Precisely because sin cannot be eradicated until the eschaton, some problems are not ultimately solvable and can only be negotiated. The alternatives have to be weighed against each other.

But could it actually happen?

One might find the case above convincing and yet still be skeptical about the prospects for anything remotely resembling economic democracy every becoming a reality. So having presented the case for why human nature is not an obstacle to socialism, let me make a few brief remarks about why the socialist vision is of value and not utterly impractical.

Every movement, organization, or ideology needs some animating vision of the end to which they are working to make decisions about how to act know. You need to know the destination to map out how to arrive. Sheldon Wolin, describing Plato's view of political theory, says that at the heart of politics is "an imaginative element, an ordering vision of what the political system ought to be and what it might become."[21] For Christians, the vision is ultimately Christ and his kingdom of God. But penultimately, we can envision how we might in the already-not-yet move toward more just and merciful systems that better reflect God’s kingdom. A socialist political economy is simply one of those penultimate proposals.

Furthermore, it is a vision which could have a surprisingly broad appeal as it cuts across the left-right dichotomies – something that more “radical” visions tend to do. It has traditionally been associated with the left, given its rejection of corporate capitalist control of the economy. But “conservative” figures should find plenty to applaud, given its skepticism of state control, an empowering of mediating institutions, and a valuing of local and traditional community and family life. Whether one’s source of political inspiration be John Ruskin’s guild socialism, G.K. Chestorton’s distributism, a Radical Orthodox post-liberalism, Noam Chomsky’s libertarian socialism, or David Graeber’s anarchism, conservatives and radicals alike should find considerable overlap in participatory socialism.

At this point, we only can get glimpses of what a participatory socialist society could look like. Orwell gave us some sense of what it briefly looked like in Spain. Individual companies, like Semco or the cooperative federation Mondragon, demonstrate that cooperative forms are possible, even in capitalist environments. The Meidner Plan in Sweden was a 9-year experiment with promising results. Most agree that there is no single blueprint and experimentation is needed to see what forms of economic democracy are appropriate in different contexts.

Having presented the negative case – that socialism is not incompatible with a sinful human nature – I should say that I believe a more ambitious case could be made that economic democracy better mitigates sin’s impact on the economy. In addition, I think it would enable more just outcomes and human flourishing than capitalist systems. But that’s an argument for another day.

About the Author

Joel Gillin is a PhD candidate in Theology at the University of Helsinki, where his research focuses on political theology. In 2022 he was a visiting researcher at Westfield House, Cambridge. He holds degrees from the University of Helsinki and the University of Colorado and his articles “Agonistic Pluralism and the Theology of Self-Revisionary Identities”, and “Religion as a Liturgical Continuum”, have been published in Kerygma Und Dogma (2021) and Neue Zeitschrift für Systematische Theologie und Religionsphilosophie (2019), respectively.

Notes

[1] For more on Maurice and his vision, see Jeremy Morris, F.D. Maurice and the Crisis of Christian Authority (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008). For a recent introduction to Christian socialism and its contemporary relevance, see Philip Turner, Christian Socialism: The Promise of an Almost Forgotten Tradition (Eugene: Cascade Books, 2021).

[2] Stephen Charles Mott, A Christian Perspective on Political Thought (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 207.

[3] See ibid. and the works of Gary Dorrien, such as Economy, Difference, Empire: Social Ethics for Social Justice, Columbia Series on Religion and Politics (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

[4] Michael Albert, Parecon: Life After Capitalism (New York: Verso Books, 2004).

[5] The differences between the Eastern and Western theological traditions and the various streams of Protestantism do not bear upon my argument. But, as I see it, even the most pessimistic of theological anthropologies – such as those of the Lutheran or Reformed traditions – are not obstacles to socialism.

[6] Michael Novak, “Father of Neoconservatives: Reinhold Niebuhr,” National Review (May 11, 1992), 39–42 (cited in Dorrien, Economy, Difference, Empire, 139).

[7] Michael Novak, The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism (New York: American Enterprise Institute: Simon & Schuster, 1982), hereafter pages cited in the text.

[8] Novak inexplicably lists “competition” among the six key Christian principles relevant for a theology of economics.

[9] Malcolm Brown, After the Market: Economics, Moral Agreement and the Churches’ Mission (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2004), 136.

[10] Larry Rasmussen, “Was Reinhold Niebuhr Wrong about Socialism?,” Political Theology vol. 6, no. 4 (February 11, 2005), 454.

[11] Reinhold Niebuhr, “The Collectivist Bogy,” The Nation 159 (October 21, 1944): 478, 480, as excerpted by Charles C. Brown, compiler and editor of A Reinhold Niebuhr Reader: Selected Essays, Articles, and Book Reviews (Philadelphia: Trinity Press International, 1992), 141–42.

[12] Reinhold Niebuhr, Reinhold Niebuhr: Major Works on Religion and Politics (New York: Library of America, 2015).

[13] Ibid., 413.

[14] Ibid., 417-418.

[15] Ibid., 418.

[16] Gary Dorrien, “Introduction,” in Reinhold Niebuhr, The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness: A Vindication of Democracy and a Critique of Its Traditional Defense (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), xx.

[17] Daniel Pink, Drive: The Surprising Truth about What Motivates Us (Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 2018). This is generally once the material/financial needs of workers are comfortably met.

[18] Mott, A Christian Perspective, 207.

[19] For example, “Mondragon limits managerial salaries to nine times that of the lowest paid member; this is an exceptionally equitable differential compared with the 2014 average CEO-to-worker pay ratio of 127:1 in Spain or 331:1 in the United States (according to the AFL-CIO).” Sharryn Kasmir, “The Mondragon Cooperatives and Global Capitalism: A Critical Analysis,” New Labor Forum vol. 25, no. 1 (2016), 52–59, at 54.

[20] Mott, A Christian Perspective, 210.

[21] Sheldon Wolin, Politics and Vision: Continuity and Innovation in Western Political Thought (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 33.